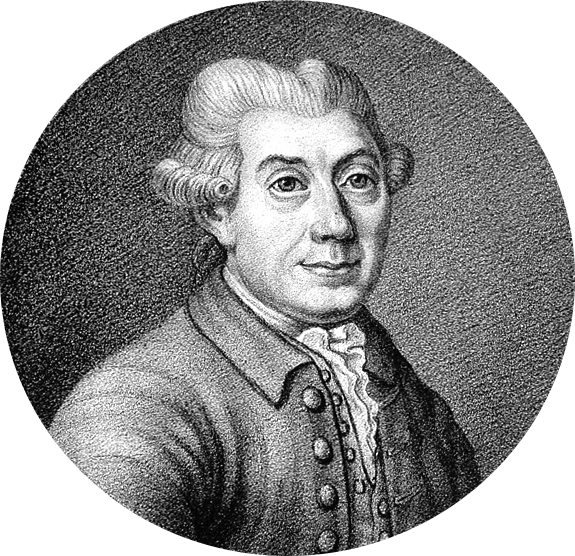

Carsten Niebuhr (1733 – 1815)

On March 17, 1733, German mathematician, cartographer, and explorer in the service of Denmark, Carsten Niebuhr was born. He is best known for his role in the decipherment of ancient cuneiform inscriptions, which up to Niebuhr‘s publications was considered to be merely decorations and embellishment.

»Since Arabia is still so little known to us, I have deemed it necessary to note not only all the villages, but also all the coffee huts that lie individually along the way.«

– Carsten Niebuhr, 1774 (Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern)

Becoming an Engineer

Nobody really expected that Carsten Niebuhr would travel to the Red Sea, to Yemen and Persepolis, making the findings of his life in later years. He grew up in a little town of religious farmers in Lüdinworth, Denmark, disliking his predicted future as a farmer himself. One day, two neighbors of the village got into a fight about their land and nobody in the entire town had the knowledge to measure the neighbors’ land exactly. Bored by his predicted future, the orphan Niebuhr left to see the world on this day to never return and study mathematics. Carsten Niebuhr wanted to become an engineer and through hard work, lots of luck and support by his teacher he was about to reach his goal.

Expedition to Arabia as Cartographer

The talented student got himself enrolled in mathematics at the Georg-August-University in Göttingen, Germany and right after graduating, he began his career as an engineering-lieutenant in Denmark. Just one year later, in 1761, the young Niebuhr started his life changing journey. Functioning as a cartographer back then, Niebuhr was part of the first scientific expedition heading to Arabia and the Near East. The actual purpose of the journey was set by Johann David Michaelis, who aimed to find proves for many stories told in the Bible. Next to Niebuhr 4 to 5 persons came along. The actual number of travelers is unknown, since some sources speak of 5, others of 6 passengers.

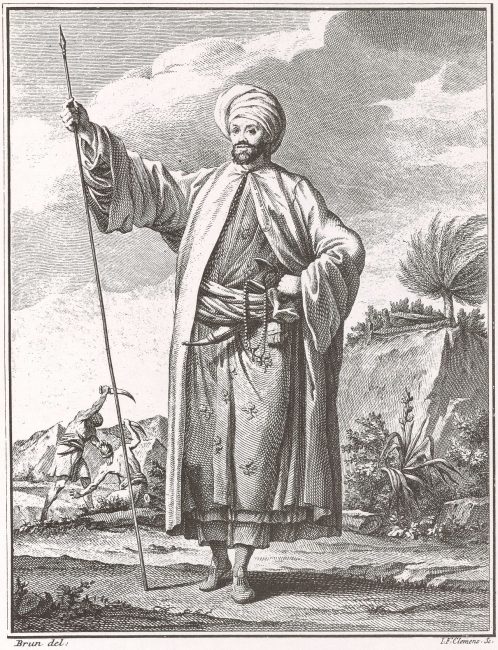

Carsten Niebuhr in the attire of a distinguished Arab in Yemen, gift from al-Mahdi ‘Abbas, Imam of Yemen

Persepolis and Cuneiform

After arriving the peninsula Sinai, the crew continued its journey traversing the Red Sea until they arrived at what is today known as Saudi Arabia. Niebuhr was able to draw first sketches of the Red Sea, used by the British post service to adjust their routes to India. Problems began to set in after they arrived Yemen. Since Malaria was back then not possible to diagnose or even be treated two crew members passed away in 1763. The rest of the team continued their way to Bombay, India. Unfortunately, further travelers died along the way and Niebuhr arrived with Christian Carl Cramer, the only doctor on board, Bombay where Cramer also passed away suffering from Malaria. However, Niebuhr was now by himself, continuing the trip to Shiraz and eventually arrived at Persepolis. The cartographer and explorer was able to copy various cuneiform inscriptions in several ruins and palaces before successfully returning to Copenhagen in 1767.

No Decoration but a Real Script

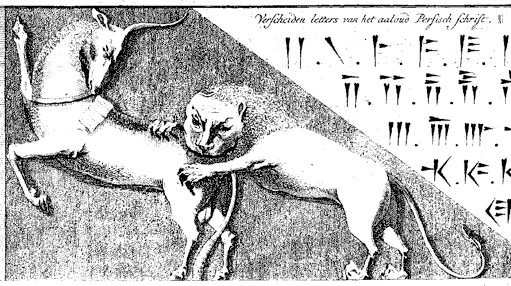

Niebuhr’s first book, Beschreibung von Arabien (Description of Arabia), was published in Copenhagen in 1772, the Danish government providing subsidies for the engraving and printing of its numerous illustrations. This was followed in 1774 and 1778 by the first two volumes of Niebuhr’s Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegender Ländern (Travel description to Arabia and other surrounding countries). These works and most specifically the accurate copies of the cuneiform inscriptions found at Persepolis, were to prove to be extremely important to the decipherment of cuneiform writing. Before Niebuhr’s publication, cuneiform inscriptions were often thought to be merely decorations and embellishments, and no accurate decipherments or translations had been made up to that point.

Cuneiform representation with unicorn and lion (Illustration from: Travel description to Arabia and other surrounding countries, Amsterdam 1779)

Awards and Merits

Niebuhr has received numerous awards for his merits and work. Professor Michaelis from Göttingen, however, was not among the congratulators. Michaelis showed practically no interest in the groundbreaking empirical findings about a world that was then largely foreign to Europeans, which Niebuhr had achieved, since he could not use them with his original intention of a collection of facts to underpin the biblical history of salvation. Due to Niebuhr’s experiences, manuscripts and sketches he collected on the way, he could complete many publications, resulting in great scientific efforts by himself and the scientific community world wide. He is now especially known for his exact copies of the cuneiform inscriptions. The history teacher Georg Friedrich Grotefend was the first person to successfully decipher Niebuhr’s inscriptions in the early 19th century.[5]

Decipherment by Grotefend

The decipherment of the inscriptions depicted quite a milestone in archeology, since explorers and scientists have been trying to reach Grotefend’s achievement for many years. Already in the 15th century, Venetian travelers brought back inscriptions to Europe. They indeed noticed the writings had to be read from left to right but never intended to decipher them. In 1634, Sir Thomas Herbert reported to have found “a dozen lines of strange characters…consisting of figures, obelisk, triangular, and pyramidal” and made first attempts reading those but never succeeded. Luckily through the carefully copied inscriptions by Niebuhr, Grotefend could determine the two mentioned kings names ‘Darius‘ and ‘Xerxes‘. Through knowing these, the teacher was then able to assign alphabetic values to the cuneiform characters.

Carsten Niebuhr died in Meldorf on April 28, 1815, at age 82.

Cracking Ancient Codes: Cuneiform Writing – with Irving Finkel, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] [In German] Carsten Niebuhr at National Geographic

- [2] [In German] Biography of Carsten Niebuhr

- [3] [In German] Durchs glückliche Arabien by Wolfgang Griep

- [4] Visible Language – Inventions of writing in the ancient middle east and beyond, by Christopher Woods

- [5] At the Beginning was a Bet – Georg Friedrich Grotefend and the Cuneiform, SciHi Blog, June 9, 2013.

- [6] Travels in Arabia from 1892, featuring Carsten Niebuhr

- [7] Beschreibung von Arabien text and illustrations at the University of Göttingen

- [8] Carsten Niebuhr at Wikidata

- [9] Cracking Ancient Codes: Cuneiform Writing – with Irving Finkel, The Royal Institution @ youtube

- [10] Carsten Erich Carstens: Niebuhr, Carsten. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Band 23, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1886, pp. 661 .

- [11] Reimer Hansen: Niebuhr, Carsten. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 19, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1999, pp. 217–219

- [12] Timeline of Explorers of Arabia, via DBpedia and Wikidata